Creativity is a term with a myriad of meanings and theories, in order to approach the subject a definition is essential. What follows is a quick literature review and my working definition for the term.

E.P. Torrance was a prolific psychologist who, from the late 1950’s, dedicated a lifetime of work to the field of creative studies, and is responsible for many theories and lab tests that continue to inform the subject. Yet despite years of researching the subject Torrance maintained that “Creativity defies precise definition.” One reason for this conclusion is that the term is used as a catchall description which is applied to just about anything positive which can be made; such as writing a haiku, painting a portrait, composing an opera, formulating a chemical equation, or developing a new sales strategy.

Rather than approach the term from a wide variety of fields (i.e. mathematical creativity, musical creativity etc.) I.R. Taylor broke down the term into 5 levels that can be used to define specific areas of creative output:

- Expressive creativity, as in the spontaneous drawings of children.

- Productive creativity, as in artistic or scientific products where there are restrictions and controlled free play.

- Inventive creativity, where ingenuity is displayed with materials, methods, and techniques.

- Innovative creativity, where there is improvement through modification involving conceptualizing skills.

- Emergenative creativity, where there is an entirely new principle or assumption around which new schools, movements, and the like can flourish.

Taylor emphasised that when talking about creativity most people instinctively use the fifth, and most rare, definition of creativity. This raises another problem with the catchall use of the word, in that when asked to think of someone creative a common response is to name a genius such as Da Vinci, Mozart, or Einstein. This linking of creativity with exceptional genius can result in the dangerous misconception that creativity is a rarefied domain of a select few, and an area which should not be approached by anyone but the gifted.

Thurstone (1952) reinforced this idea of creativity as a rarefied gift by emphasising that in order for anything to be described as creative it must meet the criteria of being new, unique, and most importantly it must be regarded as valuable to the field in which it is intended. Therefore the light bulb, the theory of evolution, the Marriage of Figaro and Hamlet can, by this definition, be regarded as creative. One problem with this definition is that very novel products can often take a long time to be accepted by their field, examples from the art world include works by Monet and Munch, and in the field of medicine can be seen in the research of Marshall and Warren, whose research took over ten years to be accepted.

In a review of popular lab tests designed to test creativity (including Dunker’s candle problem), the cognitive psychologist Robert Weisberg demonstrates that in order to solve a problem subjects first attempt to find a solution by applying existing knowledge, when this is found to be lacking attempts are made to determine and address the inadequacy. Thus the problem solving process involves a series of incremental steps whereby “The solution could be conceptualised as multiple searches of memory, in the sense that each step in the solution, if judged to be inadequate, serves as the cue for further retrieval of information.” This leads Weisberg to conclude that each step of the problem solving process can create a new problem until a solution is reached, therefore “any solutions should be considered creative, so long as they are novel as far as the problem solver is concerned.” In essence creativity is achieved if the product; albeit an idea, a painting, or a critical argument, is novel and unique to the individual.

In looking at the works of creativity as previously mentioned that satisfy Thurstone’s description we can see, similarly, that these works were not the result of superhuman leaps of creative genius, but were the result of a series of incremental insights and trials. Edison is purported to have made over 5000 (depending on the source) inadequate tests before successfully making the light bulb, Darwin reached his theory of evolution by personal reflection on previous theories by other writers including Malthus, whilst both Mozart and Shakespeare are known to have penned an inordinate amount of preliminary work which was not seen as credible to the field.

Therefore if we consider creativity as a cognitive process it seems apparent that in order to achieve Thurstone’s definition of uniqueness, one must work through a series of incremental stages whereby the results are unique to the individual. This suggests that the cognitive process involved in these great feats is the same as outlined by Weisberg and that, given the correct motivation and application, is therefore available and practiced by everyone.

My study will focus on the second level of Taylor’s model, that of Productive creativity, and specifically address the question of how play can affect and facilitate the creative process. I will be taking a cognitive approach to the subject and look at the thought process involved, in doing so I also hope to look at links between artistic creative and everyday creativity (problem solving).

Sources:

Thurstone, L. L. (1952) Creative Talent. In Thurstone, L. L. (Ed): Applications of psychology, New York: Harper & Row, pp. 18-37.

Torrance, E. P. (1988) The nature of creativity as manifest in its testing. In Sternberg, R. J (Ed.): The Nature of Creativity, Cambridge University Press, pp. 43-75.

Weisberg, R. W. (1988), Problem Solving and Creativity. In Sternberg, R. J (Ed.): The Nature of Creativity, Cambridge University Press, pp. 148-177.

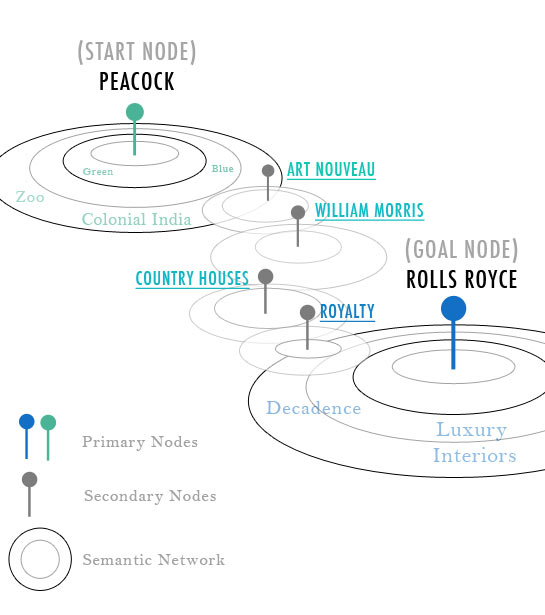

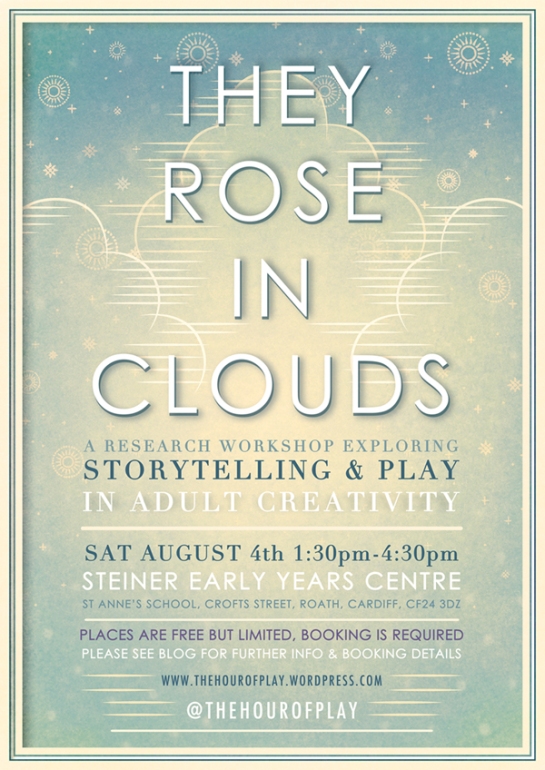

The Hour of Play is an experimental research project looking at ways in which play can facilitate creative thinking in adults. By focusing on a problem solving approach to creativity the study looks at the links between two seemingly related fields, psychoanalytical processes and the cognitive approach to creativity. Seen from a neurological viewpoint the two fields appear to describe a similar process. Both can be seen to describe creative thinking in relation to an increased access to the associative network; being described as divergent thinking in the cognitive approach and as primary process in the psychoanalytical literature.

The Hour of Play is an experimental research project looking at ways in which play can facilitate creative thinking in adults. By focusing on a problem solving approach to creativity the study looks at the links between two seemingly related fields, psychoanalytical processes and the cognitive approach to creativity. Seen from a neurological viewpoint the two fields appear to describe a similar process. Both can be seen to describe creative thinking in relation to an increased access to the associative network; being described as divergent thinking in the cognitive approach and as primary process in the psychoanalytical literature.

Finally there were items which were intended to act like small time capsules, collections of mementos from travels and adventures; these were vintage boxes and tins into which were placed period coins, pieces of ribbon and several stock photos that had been printed and distressed in order to resemble antiquated photographs. The images in these containers were intended to relate back to the association tests the participants had undertaken in the earlier stages of the workshop, and it was hoped they would act either as primers or reminders of the tests in which the associative network (and hopefully the primary process) had been triggered, therefore the images appeared related to one another by means of an undefined narrative.

Finally there were items which were intended to act like small time capsules, collections of mementos from travels and adventures; these were vintage boxes and tins into which were placed period coins, pieces of ribbon and several stock photos that had been printed and distressed in order to resemble antiquated photographs. The images in these containers were intended to relate back to the association tests the participants had undertaken in the earlier stages of the workshop, and it was hoped they would act either as primers or reminders of the tests in which the associative network (and hopefully the primary process) had been triggered, therefore the images appeared related to one another by means of an undefined narrative.